Translating Texcoco: Designing with Soil in Mexico City. MScLA Foundation Studio I HS22

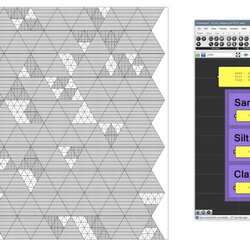

As landscape architects we are translators; we translate the complexity of spatial, temporal and relational information about the living environment to discover the hidden potentials of a place. Drawing is the language of translation. The critical act of drawing allows disparate concepts to be represented and connected across scales. By translating information through drawing, we open up new potentials for design, leading to unexpected proposals grounded in the existing conditions of a site. The act of translation through drawing makes the information from disparate fields intelligible for the process of design. Drawings speak to each other, and the conversation enables new and unexpected relationships to appear. Each line we draw contains information, and these lines are the first decisions of the design process. By making visible the invisible, and by giving voice to forgotten processes and living creatures around us, we will discover new design logics, new architectural proposals, and new ways to inhabit the planet.

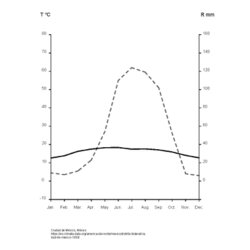

The methodology of this studio begins with an understanding of climate and geology—their performance, constraints and gifts—as the foundation for learning from the primary matter of landscapes. We believe that landscape architects can best understand the particular conditions and possibilities of one place by comparing it with other places, each with their own unique climate, geology and history. In this way, we expect to learn something about Switzerland by looking at Mexico, and to see Mexico from a unique position due to our outsider’s perspective. These tension between inside and outside, abstraction and specificity are fertile conditions for unique design proposals.

In this studio we translate the complex conditions at the intersection of Mexico City’s built environment and its geologic and climatic context. As a case study, the story of Mexico city’s urban development can be told especially clearly through the particular conditions of climate and geology in the region.

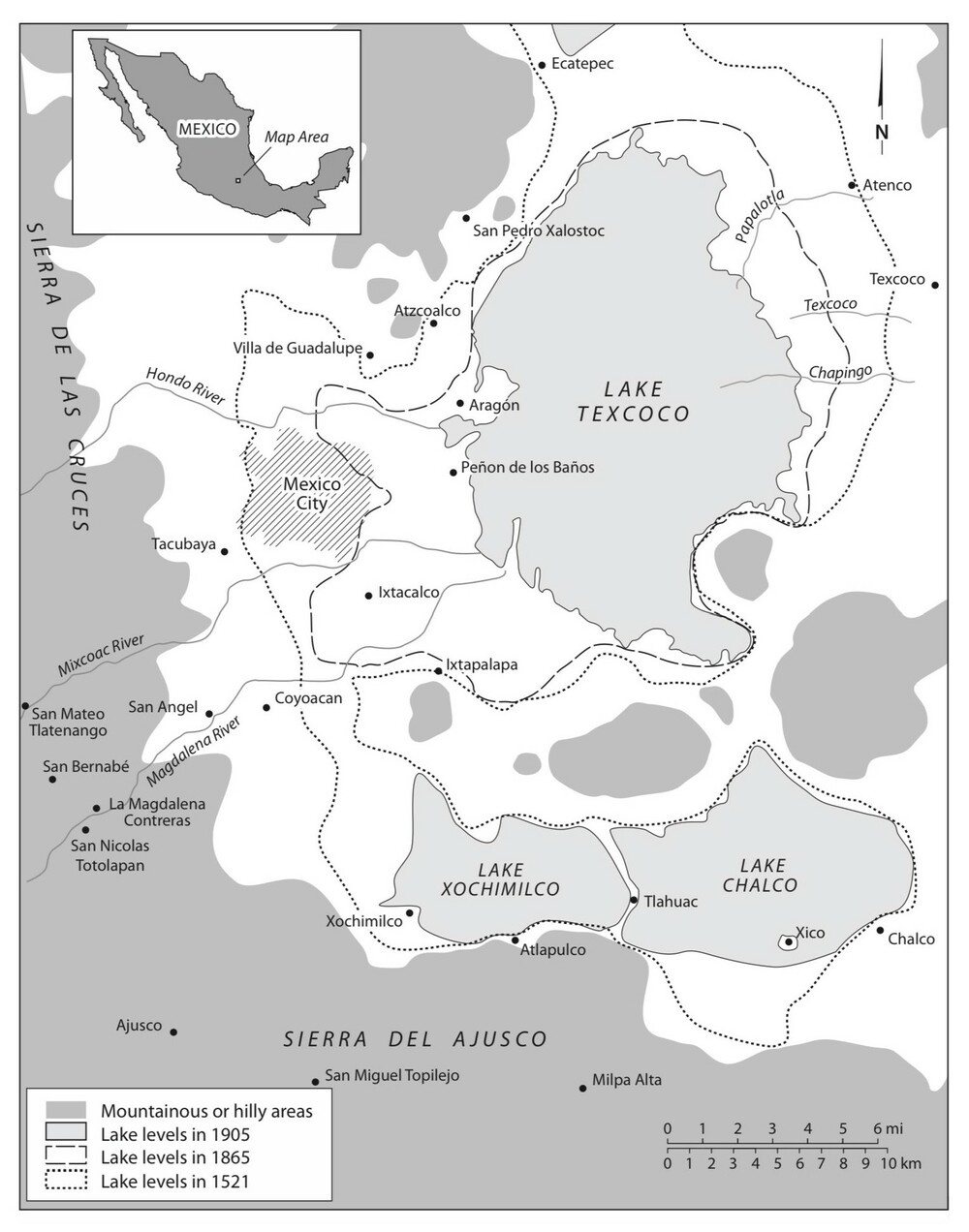

Contemporary Mexico City is built in the former system of shallow lakes that once inhabited the Valley of Mexico, a seismically active and hydrologically enclosed high-plateau basin surrounded by mountains and volcanoes. To the south of the city, the high mountains form a barrier for winter storms travelling from the Gulf of Mexico, resulting in higher average rainfall in the southern region of the city. As rainwater falls down the slopes of these mountains, the saline waters of the lakes are pushed north, creating a salt gradient in the lakes.

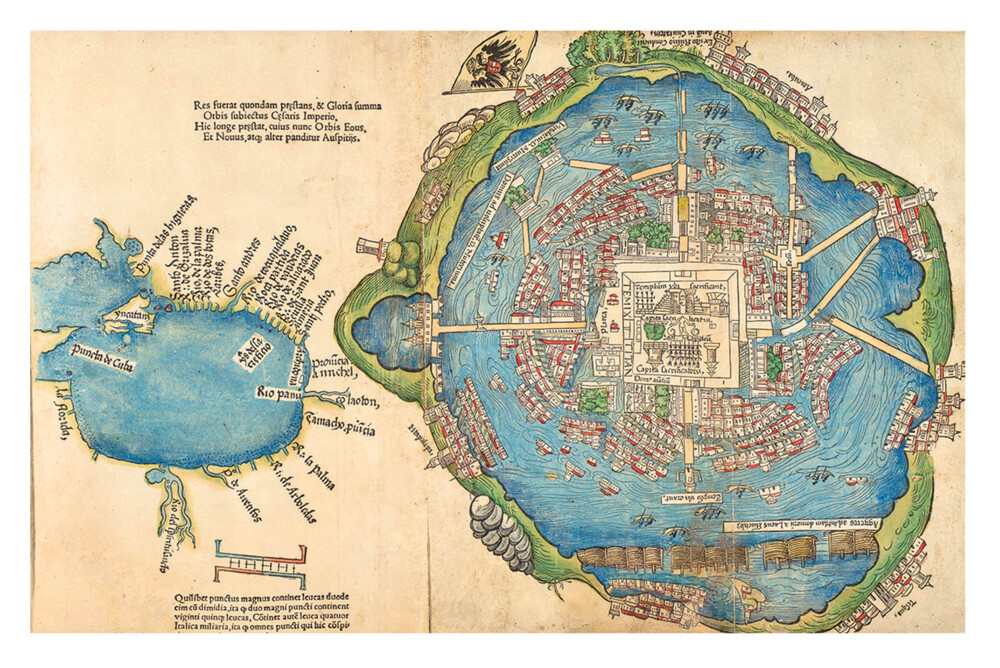

These lakes were once a key part of the functioning of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, an island city on the Texcoco lake, the largest of the five lakes in the valley. The city was connected to land via an extensive system of roads built across the shallow lakebed, and the Aztecs managed the fluctuating lake levels through an extensive system of canals, levees and dikes. In the 15th century, in order to further separate the brackish waters of Lake Texcoco from the freshwater to the south, the Aztec ruler Nezahualcoyotl constructed a 20km dike between the lakes. By maintaining the salt divide, the southern lakes were able to support extensive crop production. In Lake Xochimilco, the agricultural system of the Chinampas produced food for the population of Mexico City for centuries. In the Chinampas, the fertile soil was continually fed as sediment from the bottom of the shallow lake was dug out and added to the top of the long islands of agricultural beds.

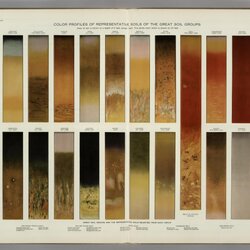

After the violent siege of the city of Tenochtitlan by the Spanish colonizers in the 16th century, a new city, Mexico City, was built on the ruins. Without adequate knowledge of the complex management of lake levels, the new city faced issues of large-scale flooding. At points during the 17th century, flood waters in some locations did not recede for 5-10 years. In response, the Spanish began draining the lakes, and over the next 500 years, drained nearly all of the five lakes. Today, the former lake beds are the site of the 22 million person megacity and, though the city was founded literally on water, Mexico City ironically now faces a severe water shortage and major issues of land subsidence. As the city extracts water from their underground aquifers, pumping at double the rate they are replenished, the clay soil dries up and compresses, causing the land to sink. Over the past century the aquifer has dropped its levels by 100m in some places, and the land has subsided 10 meters–up to 40 cm a year in some areas. Today the city, which relies on the aquifers for the majority of its drinking water, needs to import an increasing supply of water from elsewhere.

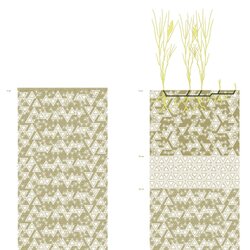

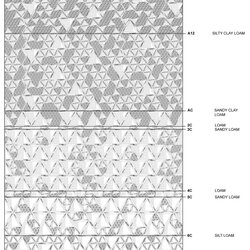

As the aquifer under the city has slowly drained, it’s been discovered that the silt and volcanic clay sediments of the historic lakebed amplify seismic shaking. These sediments are between seven and thirty-seven meters deep, with a layer of sand and rock above, and have a high water content, which makes them easily moved or compressed.. Although Mexico City is not located directly on a fault line, the geologic conditions of the city’s foundation mean that the city faces severe damage in earthquakes, notably from the 1985 earthquake to the more recent one in 2017.

Lake Texcoco, once a saltwater marsh and the largest of the 5 lakes, was the last to be drained, in 1901. Until then, the large lake was used as a dump for the city’s sewage. The lake today is dried up, and essentially a desert. Nothing grows on its bare, salty soils. This barren landscape, so close to the city center, has been the source of major dust storms, and as the land subsides, the soil at Texcoco is expected to recede 30m over the next 70 years.

Over the 20th century and still today, many have envisioned new futures for the vast Texcoco landscape – from the billion-dollar failed airport, to Iñaki Echeveria’s massive ‘ecological park’ – but, seen from Google Earth, the area remains bare, in sharp contrast with the city’s neighboring dense urban center.

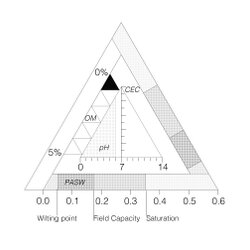

We propose that the future of Texcoco and its relationship with Mexico City can be discovered in section, by understanding the unique soils at the intersection of the city’s geologic and climatic processes. Through a series of short exercises and on-site fieldwork, we will read and translate the soils and material conditions of the former lake bed, always understanding the soil profile as part of the larger systems of the city.

Learning from the logic of the historic settlements, from the Chinampas to the 20km Aztec dam, we can discover new potentials for Mexico City’s future in Texcoco’s former lake bed. By designing with the saline soils of Texcoco and rethinking the possibilities in the dessicated lakebed, we can start to imagine new materials relationships to the rest of the city.

This studio follows an additive methodology, building on a series of precise exercises on climate, water flow and topography, soils, plants and ecology. When taken together, these exercises reveal proposals that land on site at a precise scale. By moving back and forth between learning from source material, translation through drawing, and responding with proposals, we will discover unexpected answers for Mexico City in the former lake bed of Texcoco.