Regenerative Landscapes: Rule-Based Design FS22

“Soil is a placenta, a living organism that is larger than the life it supports, a tough elastic membrane that has given rise to many life forms and has watched thousands of species from their first experiments at survival. However, it is itself now dying. A death is utterly senseless, and portends our own.” Wes Jackson, The Land Institute

The degree of exploitation of resources in the current agricultural production system and its consequences for the environment over time have exhausted the landscapes around us. However, this extended situation is not consistent around the world. Some cultures have resisted and have continued with traditional modes of cultivation with a close understanding of climatic constraints, long-term production, and limitation of resources. The practices described in this course are a collection of these marginalities, a collective knowledge that remains in remote areas of the planet. They have survived and in the last decade have been collected, reapplied, and improved again for the search of finding answers to the environmental crisis we have in front of us.

These practices suggest the need for a change of paradigm and are an attempt to bring back life in all its forms, from the soil to the atmosphere in a more integrative and holistic approach that is closer to original ecosystems. The idea of regeneration is key, even though the means to regenerate are not conclusively defined and allow for many possibilities. Based on adaptive management and understanding the potential and the limitations of the system, each of the practices respond to the limiting factors of the system and understand the key parameters that define the potential in terms of production of goods while maintaining the system alive over time as well.

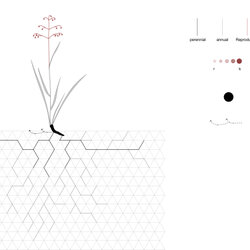

We will give students an introduction to regenerative strategies, enabling them to develop an understanding of key ecological parameters for design involving soil, animals, vegetation, and water. They learn how to identify key components of a landscape system, understand relatively why and how they work, and abstract that information in drawings and diagrams that become useful for design.

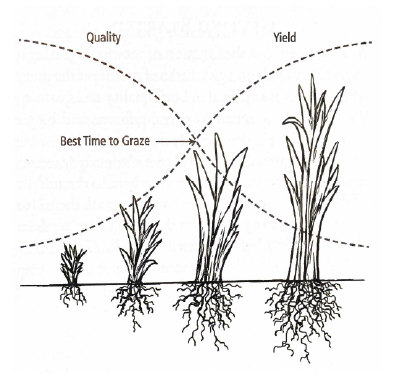

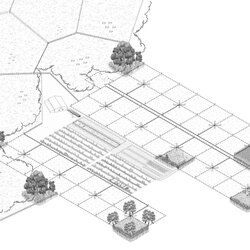

The focus of the lecture is not on the concept of regenerative agriculture, but on seven practices that are not mutually exclusive, but can even complement each other: crop rotation, pasture cropping, rational grazing, companion planting, substrates, greenhouse, and keyline. It is our goal to understand in detail how these practices work. We will present and discuss traditional and contemporary case studies that all address these seven practices in their own way.

Left: As grass grows, the volume increases, yet the quality for animals decreases. The sweet spot is somewhere in the middle, and always, a bit of moving target a good grazier aims for. Source: Steve Gabriel, 2018. Right: Chestnut orchard in Brentan, Switzerland, 1989, Source: ETH Bildarchiv.

Over the course of the lecture, we are slowly building up our main hypothesis: The combination of trees, perennials, animals, and crops is key to create a garden that works for the present, the past, and the future – and for the living, the dead, and the not-yet born. This combination is often referred to as agroforestry. Agroforestry requires a careful balance of rules, relationships, succession, life-cycles, and time scales of so many different actors of our landscapes.

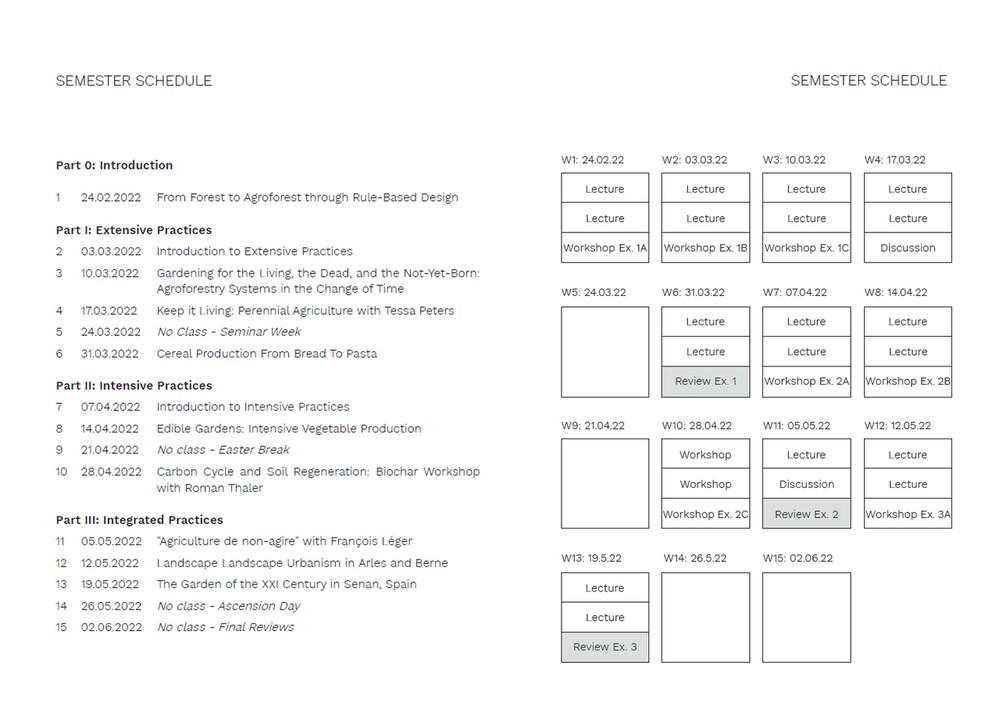

The new course Regenerative Landscapes: Rule-based Design, conducted by the Chair of Being Alive, is offered as an elective course during the Spring Semester, addressed both to students from the MScLA and MAS UTD programs.